This may be controversial, but I will say it anyway: It is time to consider whether the world needs any more iterations of the famous, done-to-death, iconic, “big landscape” compositions. An online image search using keywords like “Mesa Arch,” “Yosemite Tunnel View,” or “Tetons barn” will yield vast numbers of cookie-cutter, cliché pictures. Though some of these may be perfectly executed and may be valid as technical exercises for photographers learning the craft, at the end of the day they most often boil down to formulaic knock-offs of someone else’s original creativity. Photographs like these tell us little about the photographer’s own personal creative vision, and while they presumably seek to convey the beauty and serenity of wide-open wild landscapes, they have too often been made while standing shoulder-to-shoulder with a mob of photographers jockeying for the classic perspective.

The reality is, however, that an infinite landscape of creative compositions are out there just waiting to be discovered. Ever since I fell in love with photography about thirty years ago, I have been consistently intrigued by the unlimited potential to imagine, seek out, and create compelling abstract compositions, whether in an exotic destination or my own back yard. Using photography as a medium to create abstract images poses the obvious challenge of reckoning with the photograph’s innate descriptive nature, but that also makes success all the more rewarding. An effectively executed and compelling abstract photograph is perhaps the purest demonstration of a photographer’s original vision, understanding of fundamental aesthetics, and ability to move the viewer.

A commonly misunderstood concept, abstraction in art is all about stimulating thought and emotion using aesthetic characteristics themselves, rather than relying on descriptive information conveyed by subject content. As the painter Alan Soffer has said, “Abstraction forces you to reach the highest level of the basics.” It involves the act of prioritizing and employing essential elements such as color, tone, line, form, texture, and the fundamental graphic considerations of composition, taking advantage of human visual cognition to compel the viewer’s imagination and emotions to think and feel in response to the work, deemphasizing or stripping away features that convey explicit meaning or objective facts. Abstraction isn’t dogmatic. It doesn’t tell the viewer what to think; rather, the aesthetic aspects of the image inspire a response. A common misunderstanding is that the underlying subject matter of an abstract image must be entirely unrecognizable, but an image can be simultaneously representational and abstract to varying degrees. It is more the case that the actual identity of subject matter used in an abstract picture is largely unimportant, while the aesthetics are everything.

This of course raises the question of how to go about finding abstract compositions, and the answer is the same as it would be for any other kind of photograph: one can either go looking for inspiration and find images wherever one stumbles across them, or one can conceive pictures in advance, work out how they would need to be made, and then go out and execute them. There are, however, some practices that I employ in the search for effective abstracts. First, in advance of visiting a location, I try to identify an inventory of available subject matter and themes that interest me, seasonal phenomena, light and weather conditions, and any other elements that I might take into consideration as I conceive images. This gets amended and updated on the fly once I am on location.

Qualities of light can suggest what sort of subject matter to look for. Diffuse light—overcast, shade, light bounced off a canyon wall, flash with a diffuser, etc.—tends to work well for rendering abstract designs and patterns inherent in objects, such as rock formations, vegetation, ice, flowing water, and many macro subjects. On the other hand, the harsh contrast of direct sunlight can wreck some natural designs but creates opportunities to use light itself as the subject, such as arrangements of shapes cast by hard shadows, or patterns created by specular reflections and defocused highlights. Backlight can yield graphic silhouettes and can also be applied to good effect with fog, smoke, waves, leaves, and translucent objects.

One of my favorite ways to create abstract designs is with motion captured during long exposures—the opportunities here are limitless. We are all familiar with long-exposure landscapes depicting silky-smooth flowing water, and the same technique can be applied to create abstract designs using water, moving clouds, groups of animals, and just about anything else that will render a form or line as it moves through the frame over the course of seconds or minutes. Very long exposures (thirty seconds and more) can also be used to blur the texture of bodies of water or cloudy skies into even toned backgrounds that provide clean negative space against which other forms can be arranged. Interesting results can be yielded from the motion of the camera position itself, such as from a moving car, on a tripod on the deck of a rocking ship sailing through Arctic pack ice, or panned vertically by hand to turn an aspen forest into a series of vertical streaks.

On my last visit to the Southern Ocean, I took advantage of the brilliant pinpoint specular reflections of the sun on the surface of the waves to “carve” well-defined linear designs during a half-second hand-held exposure from the deck of the ship. Though the reflection was too bright to look at with the naked eye, a ten-stop neutral-density filter made the image possible. At the faster end of the shutter speed range, reflections in water offer all sorts of opportunities. Particularly if the surface of the water is smoothly undulating, it can be a tremendous medium for transforming reflected colors and tones in the sky, an iceberg, or perhaps a cliff-face illuminated by sunset light, into elegant and colorful patterns. Fast exposures of the sun’s specular reflections on the textured surface of a babbling brook will yield fascinating patterns that look like they come straight out of String Theory.

Another tool we can use to build abstract designs is multiple-exposure. Although this technique was once limited to either film cameras or manual layering of images in Photoshop, more and more digital cameras today permit the photographer to merge, in-camera, several frames into a single composition. This enables the photographer to layer various compositions into one, for instance, combining views of a single object or shape viewed from different orientations or shooting multiple exposures of a moving object, such as a close-up golden aspen leaf quaking in the wind, and building up an abstract pattern of well-defined edges as it twists and turns. The same technique could be applied well to reflections on water.

Color is one of the key pieces of visual information that we use to identify things that we are familiar with in the world, and eliminating it can be helpful in the creation of abstracts. Imagine a black and white photograph depicting a purely abstract design that happens to include as part of the composition a puddle reflecting a cloudless blue sky. Now, convert that same image to color. Suddenly, the viewer is provided with a key piece of information that may diminish the purity of the abstraction. For the same reason, abstracts of ambiguous shapes in clouds tend to be far more effective when executed in black and white.

Ascending Bivröst II. © 2016 Justin Black

Regardless of the techniques applied, careful framing of compositions is perhaps never more important than in the case of abstracts. Conventional styles of landscape photography often conform, more or less, to established compositional conventions suggested by the scene itself (imagine, for instance, a mountain in the distance reflected in a lake in the foreground), but abstraction is unconstrained by a need to communicate in explicit, literal terms, and thus conveys greater creative freedom, and therefore greater creative responsibility, to the photographer. In other words, the photographer has to do more of the work, since the landscape itself is less helpful in suggesting the way in which it “wants” to be photographed. Commonly, the best framing of an abstracted natural subject will critically exclude unwanted elements that disrupt the illusion of the abstract design and return the image to grounded reality.

When seeking or refining compositions in the field, I spend a lot of time moving around using my fingers as cropping tools, changing

my perspective and the crop to precisely carve out what I consider the ideal composition. In the case of the accompanying image, Ascending Bivröst II (right), rather than making a picture of Greenland’s mountainous landscape with the northern lights above, I chose to point the camera straight up into the sky to capture a more abstract, less literal image that I considered a stronger and more evocative design.

Likewise, in the case of Aasiaat Steel (left), an abstract design I carved (compositionally speaking) out of its context in a jumbled pile of scrap metal in a west Greenland harbor, I spent several minutes carefully adjusting the tripod position and framing to retain the design elements I felt were most important while distracting and overly bright background elements were kept just out of frame. The final composition involved tilting the camera off-level for the best balance and visual flow. It’s about the design, after all. The fact that I found it in Greenland is largely irrelevant to the aesthetics.

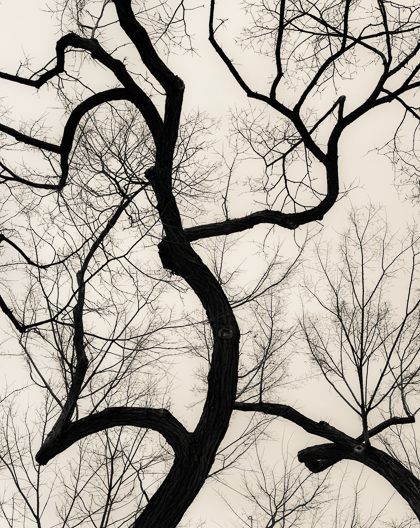

Alfred Stieglitz, an early proponent and practitioner of abstraction in photography, once said, “Wherever there is light, one can photograph,” and indeed one of the most inspiring things about delving into abstraction is that we can do it anywhere. My photograph, Siberian Elm, is a composition I discovered in a downtown park while taking a stroll through my hometown of Washington, DC. It is one of those images that is simultaneously representational and abstract, still a straight photograph of a tree, but also something else. After finding the exact position and perspective for the composition, I made a snapshot on my phone as a “sketch.” The next day, I returned with my Nikon D810, a Sigma 50mm f/1.4 ART lens, and my tripod, found the precise position again, and made five overlapping frames so that I could merge them to create a super-high-resolution file suitable for printing up to eight feet tall.

Siberian Elm, Study #1. © 2016 Justin Black

To some, the tree is clearly interpreted to be an Ent, an ancient race of walking, talking, tree-like creatures invented by J.R.R. Tolkien in Lord of the Rings. I never imagined that I would encounter an escapee from the pages of a fantasy novel just a few blocks from the White House.

The pursuit of abstraction in photography opens our imagination, raises our awareness of photographic possibilities, and makes us better photographers, regardless of what our primary interests may be. It invites viewers to use the photograph as a mirror of sorts as well, contributing something of their own to the interpretation of an image made by another person using decontextualized subject matter that ranges from somewhat ambiguous to downright unidentifiable. Personally, I’m excited to discover what new visions I might see around the next bend.