Down beneath the legs of my tripod, in the frigid, rushing flow of Bishop Creek’s middle fork, my bare feet were turning bright pink and trying to decide whether throbbing in pain or going numb was the lesser of two evils. I didn’t care much though, because I was living within an idyllic scene at 11,000 feet in California’s Sierra Nevada: fragile and elegant alpine wildflowers – “shooting stars” – bloomed beneath the cascade of Moonlight Falls, with the warm alpenglow of dawn illuminating the faces of Picture Peak and Mt. Haeckel in the background. If John Denver thought West Virginia was “almost heaven,” surely this was the real thing. What I wouldn’t know until a year later was that this moment would mark a major turning point in my life: I had just become a conservation photographer.

Shooting stars blooming along Bishop Creek below Moonlight Falls and Picture Peak, John Muir Wilderness, High Sierra, California

Photography and conservation go hand in hand. Virtually since the first collodion-process wet plates of wild landscapes were produced, photographs have been used to protect nature. In 1864, prints by Carleton Watkins were used to convince Congress and President Lincoln to preserve Yosemite Valley for posterity. His photographs were considered credible documentary records, confirming for easterners the stories of this sublime western landscape. While Watkins and his contemporary William Henry Jackson were no doubt inspired by the beauty of the wildernesses they photographed, they were first and foremost commercial photographers rather than active advocates for conservation. Their photographs were used to promote westward migration, development, and resource extraction at least as much as to inspire conservation.

The concept of the photographer as deliberate conservation communicator is a 20th-century invention. During the 1930s, Ansel Adams undertook what may have been the world’s first deliberately conceived conservation photography project, bringing to public attention the spectacular wilderness of the King’s Canyon region with the aim of protecting this Sierra Nevada wilderness from development and damming. He brought his prints and Stetson hat to Washington to lobby Congress in an all-out effort that ended with the establishment of King’s Canyon National Park in 1940. In the 1960s, Adams played a critical role in stopping Disney’s plans to develop a massive ski resort at Mineral King, a glacial basin in the midst of Sequoia National Park. He also deserves partial credit for the preservation of over 100 million acres of Alaskan wilderness, among numerous other conservation achievements. As Adams is almost certainly the most effective conservation photographer of all time, it is fitting that first award explicitly for conservation photography, created by the Sierra Club in 1971, bears Ansel’s name.

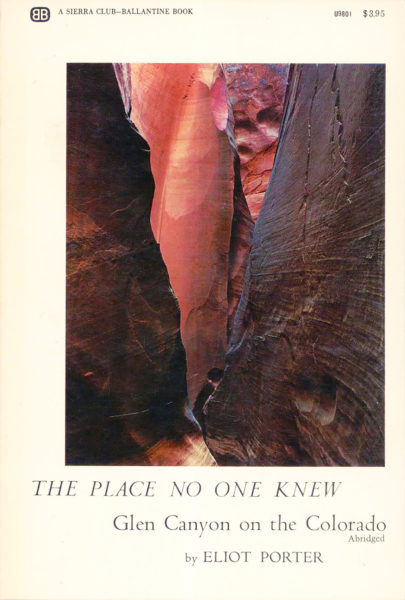

Cover of the Sierra Club battle book, “The Place No One Knew,” featuring Eliot Porter’s photographs of Glen Canyon before the dam.

During the 1950s and 60s, color photographers Philip Hyde and Eliot Porter rose to acclaim as major contributors to the Sierra Club’s “battle books” created by David Brower, the conservation group’s maverick executive director. In the process, Porter experienced a transformation from passive conservationist into an impassioned activist for wilderness. In 1970, while serving on the club’s board of directors, he wrote, “It has been said that wildness is a luxury, a commodity that man will be forced to dispense with as his occupancy of the earth approaches saturation. If this happens, he is finished. Wilderness must be preserved; it is a spiritual necessity.” These collaborations and other conservation initiatives of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s played a vital role in informing the conservationist ethics of Galen Rowell, Jack Dykinga, Frans Lanting, Carr Clifton and others who have contributed significantly to the success of important conservation campaigns and have in turn inspired countless others around the world.

My entry into the world of conservation photography came in 1999, when I went to work for Galen, a master at merging the power of photographs and words in the effort to preserve wild places, wildlife, and threatened cultures. Ever since, I have actively pursued opportunities to apply my own photography and advocacy to conservation initiatives and, in the process, have identified a number of ways that we as photographers can have an impact.

Perhaps the most straightforward method is the contribution of existing images to illustrate conservation communications projects. Whether at the local, regional, national, or international level, images are critical to informing the public, reaching hearts, and changing minds. Nothing can deliver a conservation message more quickly or broadly than a photograph, in part because photographs transcend language. Every conservation organization has a website in need of great visuals, and many produce books, magazines, annual reports, videos, and other communications tools. Among the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that have applied my stock photographs to their campaigns are Conservation International, WWF, The Sierra Club, Panthera, The Nature Conservancy, Land Trust Alliance, and National Parks Conservation Association.

More and more, however, NGOs are recognizing the value of commissioning original photography to support their campaigns, in part due to the demonstrated success of a model created by the International League of Conservation Photographers. ILCP works with NGOs to identify the sorts of photographic coverage that would be most beneficial to a given campaign and makes the connection between the NGO and a photographer, or a team of photographers, chosen from among their global fellowship who would be optimally suited to produce the needed material.

The Flathead River, one of the last undisturbed rivers in North America. iLCP Flathead RAVE, Flathead Valley, British Columbia, Canada

One such ILCP project resulted in a conservation achievement of which I am immensely proud. The Flathead River, flowing from southeastern British Columbia into Montana and onward to the Snake and Columbia Rivers, was threatened by the impending development of a mountain-top-removal coal mine within the Flathead Valley in Canada, and a group of Canadian NGOs recruited ILCP to organize a team to quickly produce coverage of this pristine headwaters region and important wildlife corridor. Several ILCP photographers contributed to the project, each with a specific assignment. For example, Roy Toft covered moose, deer, and other ungulates; Michael Ready covered the underwater riparian habitat of trout and aquatic life; Matthias Breiter covered predators, such as mountain lions and grizzly bears. My assignment was the landscape of the watershed. The resulting images were distributed to various NGO partners and put into action. One of my images of the Flathead River, for example, was published as a half-page section opener in the Vancouver Sun newspaper, the first time the threats facing the valley received significant coverage in the regionally important news outlet. With the help of our coverage, the coal mine was stopped, and the British Columbia government banned mining and drilling in the 400,000 acre Flathead River Basin.

Another memorable ILCP team project had us covering threats to the health of the largest estuary in the United States for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF). With the Chesapeake watershed spanning 64,000 square miles and parts of six states plus the District of Columbia, the participating photographers were spread far and wide, and my assignment had me driving inland, to photograph the landscape of the watershed as well as agricultural pollution near the Appalachian headwaters of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation has made widespread use of the images in their communications for several years, and ILCP produced an exhibit of large prints for CBF, which was first displayed in the grand foyer of the Russell Senate office buildings on Capitol Hill.

Pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata) blooming in Dragon Run swamp, border of Middlesex and King & Queen Counties, VA

Of course, conservation photographers more often tackle their projects alone, such as when The Nature Conservancy commissioned me to photograph Dragon Run, a large and surprisingly pristine cypress swamp on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula that they had recently succeeded in protecting within a conservancy the size of Manhattan Island., Exploring the swamp, which was accessible only by canoe or kayak, was like traveling back in time, as it looked as it would have when Captain John Smith sent an exploratory party through the area in 1607.

Sometimes, the simple willingness of professional photographers to turn their lenses toward a conservation issue can be the story that calls attention to the cause. When ILCP brought a large team of thirty photographers from all over the world to Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula for a project covering essentially the entire ecosystem from above and below ground, at sea and from the air, the response of the Mexican media was tremendous. A press conference at which most of the photographers were present, held at the World Wilderness Congress in the city of Merida, was broadcast on Mexican television, and the boost to Mexico’s relatively young conservation movement was palpable.

Of course, photographs as objets d’art can also be used to raise money for conservation campaigns. For example, during Visionary Wild’s recent ship-based expeditions in the Galapagos Islands, Frans Lanting, Tom Mangelsen, Art Wolfe, Tui De Roy, and I organized two charity auctions of our fine prints, photo books, and other items, raising over $40,000 in the process to fund conservation research by the Charles Darwin Foundation. The funds are specifically targeted to support research into the health and sustainability of habitat supporting the giant Galapagos tortoises, as well as threatened land birds, such as the stunning Vermilion Flycatcher.

Evening light skims across marine iguanas, Sally Lightfoot crabs, and lava flows at Espinoza on the shore of Fernandina Island, with Bolivar Channel and the volcanoes of Isla Isabella in the background, Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. Auctioned prints of this image raised several thousand dollars for Darwin Foundation conservation projects in the Galapagos.

This brings me to the event that, for me, drove home the power of photography as a conservation tool. In 2004, a year after I made the picture at Moonlight Falls, I was invited by The Wilderness Society to join a small group of fellow businesspeople from the small Owens Valley town of Bishop, California, to lobby members of Congress in support of a proposed wilderness expansion in the adjacent Sierra Nevada and White Mountains. Our argument was economic: the local economy was largely tourism-based, and the local backcountry and viewshed enjoyed by visitors and locals alike – indeed the very character of the place – was defined by wilderness in the mountains on either side of the valley. Regardless of whether a visitor to the area actually set foot in wilderness, anyone driving up Highway 395 through Bishop and on to the eastern entrance of Yosemite and beyond would spend hours looking up at designated wilderness in the Sierra and at de facto wilderness in the Inyo and White Mountains. The place is unique and exceptional in many ways, and in the interest of local communities and visitors alike, we wanted its wilderness character protected for the benefit of future generations.

The most memorable meeting was with Howard “Buck” McKeon (R), the Representative for California’s 25th district, which at the time was California’s largest district geographically, including much of the Eastern Sierra and stretching south and west as far as Santa Clarita. The bulk of the voters were closer to Los Angeles than to Bishop, and McKeon had not seemed particularly inclined to pay much attention to environmentalists. During the short meeting, he seemed to listen politely but reluctantly to what we had to say.

Then, I presented the congressman with a framed print of Moonlight Falls on Bishop Creek. “Did you know that this is in your district, Congressman?” I asked. Buck McKeon’s jaw hit the floor. He’d never realized that his district might lay claim to a place so beautiful. Five years later, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that Congressman McKeon had collaborated with Senator Barbara Boxer to pass the Eastern Sierra and Northern San Gabriel Heritage Act, protecting almost half a million acres of wilderness in Mono, Inyo, and Los Angeles Counties, including the proposed areas in the Eastern Sierra and White Mountains. Mind you, as with any conservation campaign, there were many people who put in a lot of hard work, blood, sweat, and tears, so I don’t for a moment believe that my picture made it all happen, but I’d like to think that a simple photograph capturing the sublime beauty of a real moment in wilderness may have helped open a certain congressman’s eyes and mind to the value of protecting wild places in their natural state.

Ancient bristlecone root structure and rainbow in a clearing summer storm, Inyo National Forest, White Mountains, California. This image shows upturned and eroded bristlecone pine roots in an area of the White Mountains near the Patriarch Grove that received wilderness designation under the Eastern Sierra and Northern San Gabriel Wild Heritage Act. It was used by the Wilderness Society to highlight the beauty and de facto wilderness status of the White Mountains.