Photographers who are consistently able to create compelling and evocative pictures with a normal lens have always impressed me. This ability can only mean a highly developed eye, in control of composition through use of camera position, perspective, light, design, and anticipation. Wide-angle or telephoto lenses, while perfectly valid and immensely useful tools, can sometimes be leaned on excessively as a sort of compositional crutch—a means to add visual drama through their significant departure from the way in which we experience the world through our eyes.

Before the invention of photography, a goal of painters was to master the rendering of natural perspective in a way that was convincing to the viewer. If the perspective felt unnatural, then the painter’s attempt to create an illusion of reality might be considered unsuccessful. While artists took all sorts of liberties in depicting stylized or idealized landscapes, they didn’t paint them with the distorted, super-wide, near-far perspective that is so popular in photography today, nor did their paintings exhibit telephoto compression or radically out-of-focus backgrounds, because neither the artist nor the audience had yet experienced the world in that way.

So, when beginning photographers ask me what lenses they should start out with, I answer with a question: “Do you want to photograph whatever pleases you for the pure fun of it (which is perfectly valid, of course), or do you want to focus on mastering composition in a way that is more deliberate?” If they answer the latter, then I recommend starting out with nothing more than a normal lens.

Lenses are considered “normal” when they approximate the length of the diagonal of the camera format on which they are being used. With the popular 24x36mm “full-frame” 35mm camera format, this diagonal measures 43mm, so, strictly speaking, a normal lens on this format should have a 43mm focal length. When Leica first popularized the 35mm-format camera in the 1920s, however, their decision to incorporate a 50mm lens into their first fixed-lens models established the standard for the “normal lens” on that format, a tradition that continues to this day.

Focal lengths close to normal (say, from as wide as 35mm to as long as 60mm in the case of the 35mm format) render the world with a naturalistic magnification and field of view similar to our main visual field, which I would describe as the area in which we can take in a scene with detail at a glance, inside our peripheral vision. As lenses get wider, they begin to noticeably reduce magnification, push subject matter away, stretch and distort shapes toward the edges, enhance diagonals toward the corners of the frame, increase apparent depth of field, and expand field of view. As lenses get longer, they increase magnification, pull subjects closer, reduce apparent space between distant objects (a.k.a. compression), flatten the impression of three-dimensional depth, reduce apparent depth of field, and restrict field of view. Normal lenses can be applied effectively to virtually any genre from landscape to reportage, and from wildlife to portraits, but because they produce a naturalistic, “no-frills” rendering, the photographer really has to do all the compositional heavy lifting. It’s nearly impossible to use a normal lens as a compositional crutch.

If we had to pick a single photographer to award the title, “Greatest of All Time,” the argument would be fierce, but Henri Cartier-Bresson would almost certainly be a top contender. Though he was uninterested in much of the technical side of the photographic process – his lab often struggled to print his sloppily exposed negatives – Cartier-Bresson was a master of composition with a 50mm lens, applied to impressive effect in fast-changing situations. On rare occasions, he sometimes used a slightly wider 35mm lens or a 90mm short telephoto, but that’s it. He essentially never used anything wider or longer than those three focal lengths, though a wide range of excellent optics were available during his long career. His portfolio demonstrates finely tuned senses of composition and anticipation that were second to none, and most of his half million negatives were made with simple 50mm Leitz lenses on Leica rangefinder cameras. Today, some avid photographers can’t imagine going out into the field without an array of lenses ranging from 14mm to 600mm for fear of missing a great composition that demands just the right focal length, despite missing many great moments while changing lenses or slowly lugging their heavy pack to the scene. In comparison, Cartier-Bresson moved unencumbered through the world with his little Leica rangefinder cameras, creating an impressive collection of exceptional pictures along the way. That’s a fact worth mulling over.

Cartier-Bresson chose the 50mm as his primary lens in part because he was a classically trained painter who had learned to see and appreciate the aesthetics of a naturalistic perspective, but also because his early Leica’s non-interchangeable 50mm f/3.5 Elmar lens gave him no choice. Like other photographers working with the relatively limited lens options available in the first half of the 20th Century, he made the most of the tool he had at hand, and in his case he mastered it. So, how does a photographer today go about becoming a master of the normal lens? Here are a few pointers. The good news is that, once learned, most of the relevant concepts can be applied to composition in general.

• Choose your “personal normal” carefully:

Many photographers who are used to the flexibility of zooms find that the 50mm lens always seems either too long or too short. If your personal way of seeing tends to favor a slightly wider or slightly longer lens, you can choose accordingly from the available focal lengths. In my own case, I find that I tend to shoot a lot of compositions at the wider end of the range from 40mm to 50mm, and far fewer in the range from 51mm to 60mm. When I choose a focal length longer than 50mm, I tend to jump to 70mm or more, so if I were to select one prime lens to cover the normal range, I’d be better suited to a 45mm than a 55mm lens.

• Camera position and perspective:

An interesting characteristic of a 50mm lens is that it can be used to suggest the look of a slightly wide or slightly telephoto lens, depending on how the photographer composes the picture. To accomplish this, you’ve got to be mobile and use your “foot zoom,” to find the right position – either one that allows the composition a little more breathing room, or that gets in tight to eliminate the extraneous. This is a good habit anyway, as changing the focal length of a zoom lens doesn’t optimize spatial relationships within the scene; it only changes the cropping of the frame around the scene. The process of optimizing the camera position and establishing the spatial relationships of your picture with a normal lens on the camera, builds your awareness of the various factors at play in framing up any composition, and that leads eventually to second-nature seeing. Eventually, it becomes intuitive to find the optimal perspective while framing the scene within the field of view of a familiar lens, without even getting the camera out of the bag.

• Did you really need all that extra real estate in the first place?

One observation I’ve made over the course of countless image critiques during our Visionary Wild workshops, is that many photographers choose by default to use a wide-angle for landscape scenes, thinking that they want to “get it all in.” The fundamental design of the composition, however, might be best served by applying the tighter field of view of a normal lens. This also has the effect of calling more attention to elements in the distance. Whereas a wide-angle pushes distant subjects farther away, the normal lens – relatively speaking – pulls them closer, and you notice subject matter that you might have missed in the wide-angle rendering.

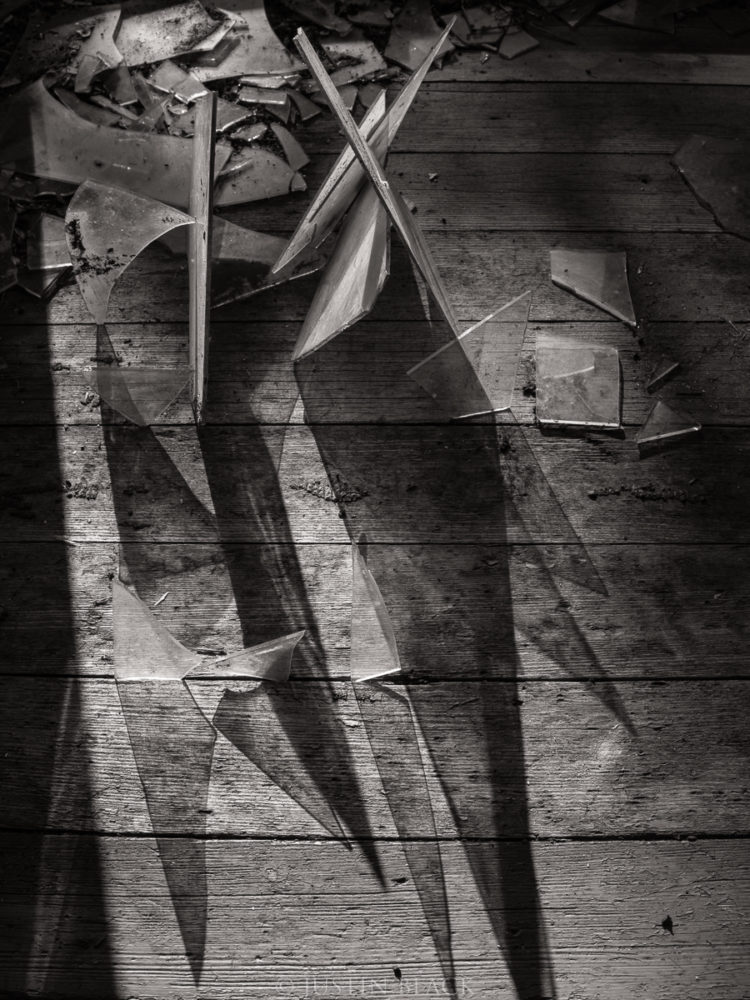

• Get close… get closer… then get inside your subject.

Robert Capa famously said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” Almost all photographers start out positioning their camera too far from their subject, incorporating distracting, irrelevant, or aesthetically unhelpful content into their composition.

To eliminate unwanted content and emphasize the main subject, we could choose to carve the composition out of the scene with a telephoto lens, but that might put unnecessary distance between the photographer and the subject. I often tell workshop participants that it can be useful to think of long lenses not as tools for bringing distant things closer; they are often best applied to making close things bigger. In other words, that big 600mm f/4 is better suited to photographing the little Blue Jay at twenty feet away than it is to photographing an elephant half a mile distant through atmospheric haze and thermal distortion (though the ability to control the background with the telephoto’s narrow field of view can be immensely useful). There is no perfect substitute for getting close, and use of a normal lens often demands that the photographer get close since zooming in isn’t an option, whether the subject is a person, the foreground of a landscape composition, an abstract natural design, or even an animal (in scenarios where this is safe for both the human and the animal). Note the intimacy of camera-trap pictures that render animals close-up with a normal or wide-angle lens, as opposed to the more detached feeling of wildlife pictures made with a long telephoto. The tele shot may show every whisker on the jaguar’s face, but the shorter focal length conveys a better sense of what it would be like to actually be there with the jaguar.

The most important aspect of Capa’s insight, however, is what he implies, which is that closeness to subject matter – in the sense of knowledge, familiarity, and emotional intimacy – will tend to give your pictures more relevance and meaning. This familiarity is usually a result of investing a significant amount of time with the subject in question. Getting physically close with a normal lens and spending time getting to know your subject in terms of both its inherent characteristics as well as its aesthetic qualities, can yield images that are beautifully designed, evocative, and full of meaning, and have a very natural feel, as if the viewer were there witnessing the scene.

• Figure-to-ground relationships:

When using the familiar, naturalistic optical perspective of a normal lens, it is especially important to pay attention to spatial relationships between elements of the scene, in order to effectively translate the three-dimensional world into two-dimensional art. Are important shapes or lines in the foreground merging with elements in the background in a way that you don’t want? Is there separation between forms and room for your eye to move between and around important shapes and lines, including the edge of the frame? You can think of “figure” as the black text on the printed page; the “ground” is the white paper on which the text is printed. In many cases this is a straightforward concept, such as when the figure is a sharp red flower and the ground is an out-of-focus green background behind it. The figure then separates strongly from the ground on the basis of color, line, and sharpness of detail. Or, the figure could be a black silhouette of a tree against the “ground” of a light grey overcast sky, in which case the separation is the result of differing luminance.

• Effects of depth of field:

Normal lenses are long enough that they can effectively create visual separation of nearby foreground subjects by blurring backgrounds when their large maximum apertures (typically in the range from f/1.2 to f/2.0) are employed. Likewise, they are short enough that they have good hyperfocal depth-of-field characteristics, enabling you to keep everything sharp from near to far using a small aperture like f/16.

These lenses are generally among the very best and most affordable optics available to us. While premium models like the Zeiss 55mm f/1.4 Otus and Leica 50mm f/2.0 M-Apo-Summicron achieve near optical perfection and are built to last a lifetime or two – with stratospheric prices to match – all the major manufacturers make excellent normal lenses at a fraction of the cost, and many are downright bargains. Newer models taking advantage of the recent revolutionary advances in computer-aided lens design will tend to offer the best optical performance. One of my favorites is Sigma’s Art Series 50mm f/1.4, which delivers superb image quality on the highest resolution sensors, quick autofocus, and weather sealing, at a quarter the price of the Otus. Even entry-level lenses under $200 offer excellent performance, so there’s a “nifty-fifty” for everyone. By the way, those 85mm and 90mm tilt-shift lenses from Nikon and Canon can be used to make super-high-resolution compositions with a normal-lens perspective, by shooting overlapping frames using their shift function, and stitching the images together in Lightroom.

Of course, normal lenses aren’t always the answer. While a photographer working in a controlled environment like a studio can tailor the scene to suit the field of view of the lens, photographers of the natural world often need a wide array of focal lengths to tackle scenarios in which nature sets the scene and wields more control than we do. It’s interesting to note, however, that a casual survey of contemporary art photography that is exhibited in major museums will quickly reveal that the bulk of this work is made with normal or near-normal focal length lenses. Moderate wide-angle lenses are commonly used as well, and sometimes a short telephoto, but a fairly common characteristic of high-end art photography is that it is typically rendered using a rather naturalistic perspective that rarely calls much attention to the focal length of lens used. One hardly ever sees a picture that bears the tell-tale signs of a long telephoto or a super-wide lens hanging in the Museum of Modern Art in New York,