The very American artistic tradition of celebrating the concept of wilderness, associated so closely with photographers like Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, reached an early zenith in the mid 19th century with the Hudson River School painters. Their work attempted to capture exceptional qualities of light, topography, and weather to render idealized visions – not always too far from the truth – of sublime landscapes across the continent, from the Catskills to California, in which humanity is often permitted to be present but never dominates.

It is hard not to characterize the light captured with oil on canvas by the likes of Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Church, and Sanford Gifford as “photographic,” while we often refer to comparable light in photographs as “painterly.” We still see and photograph similarly sublime scenes in wild areas across America today. A key difference is that the Hudson River School artists experienced a view of nature and our place in it that was entirely new in the context of their time and culture, though today, our vision still works the same way theirs did 150 years ago.

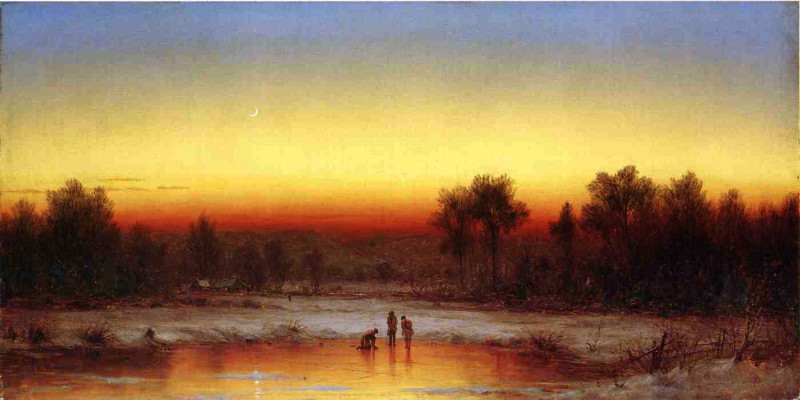

In fact, a piece by Gifford once helped to open my eyes to the way we see and go about capturing images of the world around us. His painting, A Winter Twilight (1862), depicts three tiny figures on a frozen pond, with a fence line and shrubbery in the foreground, and a row of trees in the background. The trees’ bare branches are silhouetted against a colorful evening sky. Something about the way the artist rendered the highlights and shadows in the image seemed oddly familiar…

Back in the film days, frustration with the limited range of tones that photographers’ could capture led to the development of solutions like graduated neutral density filters that enabled us to easily balance differences in brightness between two or more areas of a composition. The apparent flaw of grad ND filters, however, has always been that when an object is itself entirely in shadow but crosses over from dark to bright backgrounds within the composition, the filter gives away its effect because the section of the object that is against the brighter background (the area being darkened by the dense part of the filter) ends up going black, while the part of the same object that falls against the shaded background (not being effected by the filter) shows good mid-tone detail.

In Gifford’s painting, objects in the area of shade at the bottom of the painting displayed good shadow detail, while the tops of the trees against the brighter sky were painted as black silhouettes – exactly like the effect I had seen time and time again in color slides made using a graduated neutral density filter. Why would Gifford paint the tops of his trees black when good detail is readily apparent in similarly illuminated subject matter within the scene? He had never seen a color photograph, much less the effect of a grad ND filter.

Without resorting to complex darkroom masking, a film photographer attempting to render good color saturation in the bright sky behind the trees would have had no choice but to force the silhouette and the accompanying loss of detail in the branches. Gifford on the other hand, with the unrestricted palette of artistic freedom at his command, chose to paint the trees this way. It’s the way he visualized them and what looked most natural to him as he applied paint to the canvas.

To put it simply, a silhouette of branches against the sky is precisely how he saw it – and how any of us would see – despite the fact that the light source for the illumination of the treetops is the same as that in the shadowy parts of the scene that he chose to paint a bit lighter and with good detail. This makes sense: when we look at an object illuminated by diffuse indirect light against a dark background, our visual system sees good detail in it. The same object illuminated by the same light but against a sufficiently bright background will look black as our visual system responds to the increased overall brightness. This is precisely the reason why, when used carefully, graduated neutral density can make an image look more like what we saw with our own eyes.

Fast forward to the present day. Finally, digital technology empowers photographers in the early 21st century with a degree of control and creative freedom comparable to that of a 19th century oil painter. In comparison, however, photographers have it easy. No need to sketch numerous detailed studies in the field for later use as artist’s references in the creation of the final piece, and no need to labor for weeks on end to complete a single finished work.

The tradeoff of course for powerful and easy to use digital tools is a greater burden of creative and aesthetic judgments. As wonderful as they are, all the array of technological tools at our disposal are only as good as the eyes and brains used to apply them. High dynamic range processing (HDR), for example, can create visually striking images, but the lure to routinely over process can be seductive. When technology guides the creative process rather than serving as a tool under the thoughtful control of the artist, we can experience more difficulty in aesthetically and intuitively accepting an over-manipulated photograph of a real scene than we do a naturalistic 19th-century oil painting of a scene that only ever existed in the artist’s mind.

HDR and other useful new tools are not the problem, but we are faced with a tremendous array of decisions that influence the quality, relevance, and character of our work. We take for granted the immense power of post-production tools that enable us to radically lighten and enhance detail in a shadow area – that back in the film days might have been rendered as pure black by default – while simultaneously rendering finely detailed bright highlights. We have the technology to do it, but one has to carefully consider when, how, and how much to use the tools in the digital toolbox, and whether each modification really serves the image. We can boost saturation and contrast of the most banal composition to the point that it grabs visual attention, but will it mesh with our visual intuition and actually hold up aesthetically over the long term?

Finding ourselves with complete and easy control over the color and tonal value of every pixel in every photograph we produce, photographic artists can enjoy the freedom of total creative license. Like a painter, we have the option to render the treetops as silhouette, or instead can choose to depict them as richly detailed mid tones against the same bright and vibrant background. Gifford conspicuously chose the approach that is more in accord with naturalistic visual perception despite his ability to have depicted it any way he wished.

In the context of a world filled with high-definition digital animation and fantasy photo-illustration, it is truer than ever that the most meaningful nature photographs will be those that inform us regarding real nature and our relationship to it. These images may be spectacularly beautiful; they may reveal situations, phenomena, and juxtapositions in nature that seem unbelievable, uplifting, or devastatingly depressing; but the greatest power of nature photography stems from the trust that the image we find so compelling is also representative of another human being’s authentic experience.

Interestingly, A Winter Twilight doesn’t depict an actual event in time and space. Concealed by Gifford’s naturalistic rendering of light and tone is the fact that it is an imagined composite of real situations that he sketched in various locations and at all hours of the day rather than during the fleeting twilight depicted in the final painting. His highly tuned ability to see and visualize a final composition, however, enabled him to create a fairly convincing illusion of reality back in his New York studio. Though we photographers work more in the moment, we can still learn a great deal from the impressive visual intuition, understanding of light, and thoughtful aesthetic choices demonstrated by Gifford and other painters like him. As fast as the times, technology, and tastes may change, we share profound connection with our antecedents through the human visual system.